The Jemmy Button Story: A Kidnapping, a Hoedown and a Massacre in Wulaia Bay

Travelers on our Patagonia cruises know they will be visiting some of the most remote glaciers, fjords and islands of southern Chile, but many don’t know that they’ll also be visiting the Yahgashaga: the homeland of the Yamana indigenous people of Tierra del Fuego, and the scene of an incredible 19th century true story that includes a kidnapping, a hoedown, and a massacre. The star of that story is a young Yamana man born Orundellico in 1815, but renamed Jemmy Button when kidnapped by British Captain Robert Fitzroy in 1830. Jemmy would go on to attend school in Walthamstow, England, become friends with a young scientist by the name of Charles Darwin, and eventually be accused of orchestrating a mass murder back in Wulaia Bay, the last stop before Cape Horn on all of our Patagonia cruises.

In 1815, when Jemmy was born, though Europeans including the Spanish, Dutch and English had sailed through the waters of Tierra del Fuego, none of the colonial powers had staked a defensible claim to this chain of islands that form the southern tip of South America, nor had the newly-independent republics of Chile and Argentina. Yahgashaga remained Yamana territory, and Jemmy was raised in the traditional Yamana way, canoeing with his family from beach to beach. The men made fires, hunted seals and built wigwams on the shore, while the women handled the more water-based tasks: diving to the ocean floor to gather shellfish, mooring the canoes in nearby kelp forests and swimming ashore in the frigid waters to join their families at the fire on the beach. The Yamana people were mostly naked, occasionally wearing a seal skin or guanaco (similar to a llama) hide over their shoulders or covering their skin with blubber to keep warm in the blustery weather of this southernmost landmass before Antarctica.

Into this scene sailed Capitan Robert Fitzroy in 1830 aboard the HMS Beagle, commissioned by the British crown to map the southern coast of South America. Kidnapping Fuegians (a general term used for indigenous people of Tierra del Fuego) was not part of Fitzroy’s orders, but when members of the nearby Kaweskar tribe, a rival of Jemmy’s Yamana tribe, stole one of the Beagle’s whaling boats, Fitzroy strayed from his orders of geographic exploration and began kidnapping Fuegians. Initially his intention was to hold them ransom until his whaling boat was returned, but when that didn’t work, he decided to keep them, bring them to England, teach them English, Christianize them, and then bring them back to Tierra del Fuego. His hope was to create for England, and for the Church of England, some “civilized” allies and a foot in the door of this hitherto unconquered land.

Jemmy paddled in the canoe with his family out to meet the British visitors and see if they could barter some fish for a useful European tool. While the Yamana people did not speak any European language, many of them did know the word cuchillo, Spanish for knife, which they’d learned trying to trade with passing-by Europeans. As the Yamana men’s responsibilities included carving up beached whales for blubber, one can only imagine how useful a knife would have been to them. However, instead of getting a knife, Jemmy’s dad was handed a shiny mother of pearl button and Jemmy was plucked out of his Yamana canoe and plunked down into the British dinghy, in what Fitzroy described as a trade, but a modern reader of this story, including Fitzroy’s surviving journal and firsthand account of this event, can only interpret as a kidnapping. Thus Jemmy was given his new last name Button, an homage to the trinket for which he was “traded.”

Fitzroy’s report from this day, May 11th, 1830, reads: …we continued our route, but were stopped when in sight of the Narrows by three canoes full of natives, anxious for barter. We gave them a few beads and buttons, for some fish; and, without any previous intention, I told one of the boys in a canoe to come into our boat, and gave the man who was with him a large shining mother-of-pearl button. The boy got into my boat directly, and sat down. Seeing him and his friends seem quite contented, I pulled onwards, and, a light breeze springing up made sail. Thinking that this accidental occurrence might prove useful to the natives, as well as to ourselves, I determined to take advantage of it. The canoe, from which the boy came, paddled towards the shore …

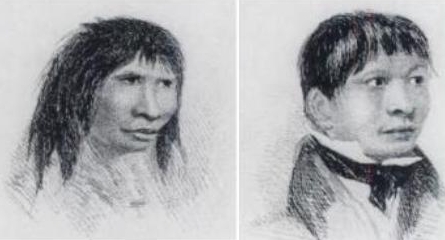

On board the Beagle, Jemmy met three other Fuegians who had already been kidnapped and had likewise been given names connected to their kidnappings. A 26 year old man was named York Minster because a rock formation near where he was kidnapped resembled the cathedral in York to the British eye. A 20 year old man was donned Boat Memory since he’d been stolen in revenge for the stolen whaling boat. And an 11 year old girl was given the name Fuegia Basket, for she was a Fuegian kidnapped from a place where the Brits had weaved themselves a basket-style boat.

The four Fuegians arrived to Plymouth, England in October 1830 and by November, one of the four, Boat Memory, died of smallpox. Rather than this young man’s death being a warning to Fitzroy and his contemporaries that increased contact with this remote, largely uncontacted group of indigenous people would only lead to Old World diseases bringing about their eventual decimation, Fitzroy continued with his plan to “civilize” the remaining three Fuegians. Jemmy, York and Fuegia were placed in the Walthamstow Infants’ School, a coach ride through industrial revolution-era London to the countryside just northeast of the city. Their curriculum consisted of walking, clapping, chanting and singing. Jemmy and Fuegia, both under 16 at the time, took well to learning the English language and seemed to adapt well to their new surroundings. The 26 year old York Minster, however, was labeled “antisocial.”

They were dressed in British clothes and became something of a curiosity in high society, even being taken to the palace in London to meet King William IV and Queen Adelaide, who gifted Fuegia Basket one of her royal bonnets. Pomp and circumstance aside, these were human beings, and whether proper or not, York began to take a liking to young Fuegia, which worried Fitzroy, a conservative Christian striving to keep his place in the who’s who of the British royalty. How a romantic relationship between a 26 year old kidnapped “savage” man and an 11 year old kidnapped “savage” girl would play out and be viewed by British society weighed heavily on his conscience, and he began to expedite his plan to return the three Fuegians to Tierra del Fuego.

In December 1831, at Fitzroy’s beckoning, the British navy commissioned a second voyage of the Beagle, and this time Fitzroy would be accompanied on board by a young naturalist named Charles Darwin. Darwin’s account of the voyage of the Beagle included some detailed passages about the Fuegians, especially Jemmy Button, whom he befriended, and as Darwin’s writings would later become published and well-read, Jemmy’s celebrity would grow, for better or worse.

Darwin wrote of Jemmy:

‘the expression of his face at once showed his nice disposition. He was merry and often laughed, and was remarkably sympathetic with anyone in pain… When the water was rough, I was often a little sea-sick. Jemmy used to come to me and say in a plaintive voice, “Poor, poor fellow!” but the notion, after his aquatic life, of a man being sea-sick was too ludicrous, and he was generally obliged to turn on one side to hide a smile or laugh, and then he would repeat his “Poor, poor fellow!”’

The Fuegians were returned to Wulaia Bay, in the Yamana’s Yahgashaga homeland, and for a moment it seemed this story may have a happy ending. The plan was to leave Jemmy, Fuegia and York with a young missionary named Richard Matthews, and upon arrival to the beautiful cove, near where Jemmy had originally been picked up, the British began to go about building a mission hut. Hundreds of indigenous people arrived in dozens of canoes to see what happening on the beach and Jemmy was reunited with his family. By one account, two of the Englishmen, a mate and the surgeon, entertained the crowd of Fuegians by playing the jaw harp and teaching the locals some dance moves, which they enthusiastically imitated. This British-Fuegian hoedown, however a happy moment, would not be the happy ending to this story of kidnapping and Christianization. The fledgling mission was overrun by looting indigenous people, who had a completely different concept of personal property than the Europeans. Matthews abandoned the mission and rejoined the Beagle, York and Fuegia left Wulaia Bay and returned to Kaweskar territory, and Jemmy was left to return to his native state.

Darwin wrote: Every soul on board was as sorry to shake hands with poor Jemmy for the last time, as we were glad to have seen him. I hope and have little doubt he will be as happy as if he had never left his country; which is more than I formerly thought.

Over 20 years later, a group in England that called itself the Patagonian Mission Society, could not resist the allure of finding Jemmy Button, the English-speaking Fuegian they’d read about through Darwin and Fitzroy. They sought to use him to help them establish a Christian mission in Tierra del Fuego to convert the Fuegian peoples. Amazingly, in 1855, a ship of the Patagonia Mission Society called the Allen Gardiner sailed back to Wulaia Bay, managed to find Jemmy, and eventually in 1858 convinced him to take his family to the Falkland Islands to the Christian Mission they’d established there. After about a year in the mission Jemmy and his family returned to Wulaia Bay and the British took another group of Fuegians to the Falklands. Upon their return in 1859 they again attempted to establish a mission at Wulaia Bay, this time with tragic results.

Author Nick Hazlewood describes the carnage in his book Savage, The Life and Times of Jemmy Button:

Out on the ship,

Alfred Coles looked up from the galley where he was preparing lunch, and saw

the Yamana rise. ‘They are up to mischief,’ he said to himself. A group of

naked men approached the unguarded boat, removed its oars and carried them off

to a wigwam. The hymn singing stopped, and a dreadful noise pierced the air.

Coles turned his gaze to the house. A large group of Indians were attacking it,

smashing down the door, flooding inside. Hugh McDowall, the veteran sailor and

one-time Arctic explorer, was clubbed to the ground. Seven unarmed men pushed

their way out of the house, only to find a huge mob waiting. Wooden clubs

carved from the branches of beech trees whipped down, cracking skulls, a rain

of stones darkened the sky and thudded against the heads of the fleeing crew.

The two Fell brothers, snared by a circle of Fuegians, fought and dropped, back

to back; boulders continued to batter their lifeless bodies. The carpenter and

two men fell under the dull bludgeoning of clubs. Along the beach Ookoko ran up

and down crying, hands held out in front of him, imploring the assassins to

stop. From out of the crowd burst the Swedish sailor, August Petersen, and the

screaming catechist, Garland Phillips. At the water’s edge a boulder flattened

the Scandinavian. Phillips plunged into the sea, black hair flapping in the

wind, mouth contorted in anguish. He tried to launch a canoe, but as he pushed

desperately, up to his knees in water, Macalwense, the Fuegian known to the

missionaries as Billy Button, threw a stone that crashed against his temple.

His head lolled to one side, then to the other, and finally his legs buckled

under him as the life drained from him, his coat tails rising on the ebb of a

reddening sea. There were eight men dead on Wulaia Cove.

The only European survivor of the massacre at Wulaia Bay, Alfed Coles, was eventually rescued by another ship from the Falklands, and he blamed Jemmy Button for killings, saying he and his family had orchestrated the brutal attack. Jemmy maintained his innocence and was taken to stand trial in the Falklands where he was eventually acquitted, but in a way the jury is still out on Jemmy’s legacy. Was he a gateway between two cultures, a mass murderer, or a freedom fighter trying to prevent the establishment of a foreign mission in his homeland?

Shortly after all of this drama in Wulaia Bay unfolded, Jemmy died of an unknown disease, as various unknown diseases, presumably the result the increased contact with the Europeans, swept through and devastated the indigenous population of Tierra del Fuego. Their population continued to decline in the following decades, with a huge wipeout occurring following the British establishment of a mission in nearby Ushuaia, which was incorporated by Argentina in 1884, leading to more contact and more diseases. By the end of the 19th century the Yamana and the other indigenous groups of Tierra del Fuego were being hunted into extinction by prospectors and sheep ranchers. By one account, today there is only one surviving full blooded Yamana indigenous person, a woman named Cristina Calderon, who lives in Puerto Williams, Chile, in Tierra del Fuego.

Today no one lives in Wulaia Bay. Our Patagonia cruises stop there and one could mistake the gorgeous bay as a pristine cove devoid of human history. However, the story of Jemmy Button reveals this to be the site of a kidnapping, hoedown and massacre that are weaved into the story of Darwin, the ambitions of the British missionaries and a dark chapter in human history: the genocide of the indigenous people of Tierra del Fuego.

For more on Jemmy Button’s story, check out The Skinny Country Podcast Episode 1